Bolster investments in children and families to protect Washington’s future

While the youngest Washingtonians have so far been largely spared from some of the worst health impacts of the COVID-19 crisis, the toll of the pandemic on the well-being of children and their families should not be underestimated. Prolonged school and child care closures, lost jobs and incomes, and the added stress of balancing these losses are harming families. And while some of these disruptions may seem short-term, they have the potential to affect the well-being of kids for years to come.[1]

Due to its disparate effects on Black, Latinx, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander, American Indian and Alaska Native people in Washington state,[2] the pandemic has most deeply harmed kids of color, children in immigrant families, and children in Indian Country – especially those whose families were already struggling to make ends meet. Decades of racial inequities and discrimination in our education, employment, housing, immigration, financial, health, and criminal legal systems have catalyzed the disproportionate health and economic impacts of COVID-19 on these communities.

Given the magnitude of the pandemic, federal and state lawmakers must act with urgency to support kids and families and ensure their long-term well-being. In the sections below, we highlight five pressing challenges facing Washington’s kids and their families amid COVID-19. Families are facing the mounting stress of job and income loss, putting them at greater risk of homelessness and food insecurity; the state’s already stressed child care infrastructure is at risk of collapse; school closures are impeding children’s educational progress while many families lack access to remote learning technology.

These challenges cannot be met with short-sighted cuts to vital services, as recent experience has shown. During the Great Recession, the state’s short-sighted response weakened families’ ability to meet their basic needs. Repeating this all-cuts approach in response to a health and economic crisis would deepen harm to the children and families who are already bearing the brunt of the pandemic’s impacts and could create losses from which the state struggles to ever fully recover. Instead, state and federal lawmakers must protect families from harm by supplying vital income, health, housing and food supports, ensuring that child care small businesses can reopen and remain open, and expanding access to remote-learning technology. These efforts require additional federal aid to state, local, and tribal governments as well as bold action to raise progressive revenue at the state level, so that lawmakers have the resources needed to equitably invest in Washington’s communities.

A Note About the Data:

Wherever possible, data are disaggregated to provide a preliminary understanding of disparities by race, ethnicity, and nativity. Data are not always available for all races and ethnicities — a troubling fact in light of our country’s long history of cultural erasure. Data about gender are also rarely available for transgender and nonbinary people. The terminology used by data sources to describe people’s identities can also be limited and/or inconsistent. As a result, the statistics throughout this report tell a limited story. And in some cases, the numbers don’t reflect people’s lived experiences.

This report draws primarily from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, launched in April, which provides near real-time data on how the COVID-19 crisis is affecting the nation. While these data offer important insight, the survey has significant limitations – including that it fails to disaggregate data for American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander groups. Broad race categories – like the aggregate “Two or more races + Other races” category – mask important differences and distinct experiences across diverse groups of people.

KIDS COUNT in Washington is committed to continuing to engage with the communities represented in these data to better understand the stories, voices, and people behind the numbers. We are also committed to engaging with the communities left out of this data – as well as to advocating for better, more accurate, more inclusive data.

1. Job and income losses

As the COVID-19 economic crisis continues to unfold, families across Washington state are grappling with the increasingly profound challenges of putting food on the table, keeping a roof overhead, and meeting other basic needs. Unprecedented job and income losses have pushed a large and growing number of children and families across Washington state – especially those who are Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) – into acute economic hardship. The impacts of the recession have fallen hardest on Washington families who were struggling to make ends meet even before the onset of the pandemic – held back by rising income and wealth inequality and institutional racism.

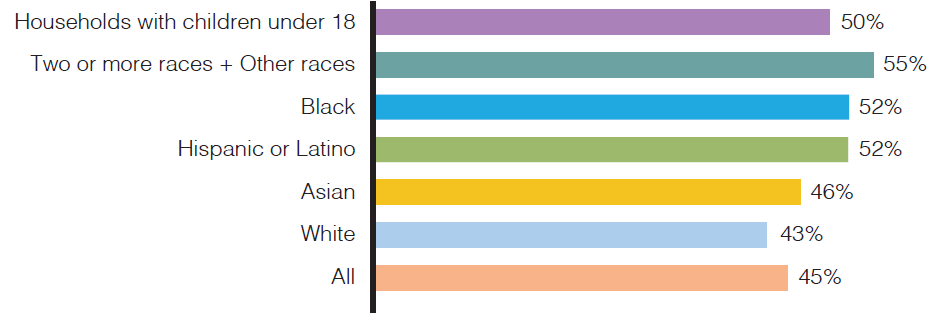

Recent data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s weekly Household Pulse Survey show that fully half of Washington adults in households with children have lost employment income since March 2020 – more than their childless counterparts and the overall state population.[3] Household expenses are also on the rise due to the pandemic’s effects on the cost of groceries,[4] utilities,[5] and the transition to remote learning.[6] As a result, about one million adults in households with children are struggling to make ends meet.

While income losses have been widespread, BIPOC households have shouldered a disproportionate burden. In Washington state, about two in five (43%) white adults report that their household experienced income losses since March, while more than half of Black, Latinx, and American Indian and Alaska Native, Pacific Islander and Native Hawaiian, and multiracial adults report lost household income.[7] These trends reflect the concentration of many Black and Latinx workers – especially those who are women – in lower-wage work, where job losses have been larger than in higher-paid industries.[8],[9] Employment discrimination, occupational segregation, inequitable education policies, and policies that have systematically devalued certain kinds of work[10] make BIPOC workers more likely to experience wage cuts and job losses – and COVID-19 has deepened this economic vulnerability.

BIPOC households and households with children are facing the greatest income losses during COVID-19

Percent of adults saying that their household experienced loss of employment income between March 13–September 28, 2020, Washington state

A sharp increase in need for public supports like cash and food assistance also reflects the depth of the crisis. Since the beginning of the outbreak, the number of families participating in Washington’s WorkFirst/Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program – which provides cash assistance and supportive services to families with children living on very low incomes – has increased by nearly a quarter (about 6,000 additional families).[11] Nearly 63,000 additional individuals and families are now receiving food assistance through Washington’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) – a 13% increase since February 2020.[12] Increased caseloads signal that cash and food assistance are working as they ought to, helping to blunt the worst effects of the crisis for those experiencing job and income loss and other forms of economic destabilization.

In response to budget shortfalls in the wake of the Great Recession, Washington state policymakers enacted deep cuts to cash and food assistance programs – prolonging the recession for the state overall and stripping basic support away from those hardest hit by the financial crisis. State policymakers pushed more than 20,000 families off of support and into deeper economic hardship between 2008 and 2016 by restricting access to WorkFirst/TANF.[13] Lawmakers also cut the assistance available through Washington’s Food Assistance Program, which provides support to some immigrant families who are not eligible for SNAP. Many cuts have remained in place, so that public support programs never fully recovered from the austerity budgeting of the Great Recession. As policymakers confront a new shortfall, they must chart a different course – one that prioritizes resources for the people and families most impacted and sets our state up to thrive long-term.

Economic insecurity can have lasting consequences on child well-being, harming kids’ physical and emotional health and undermining their ability to succeed in school and later in life.[14] Families who are struggling to afford rent, nutritious food, diapers, and other essentials – against the backdrop of disruptions to school and the danger of the coronavirus itself – are also navigating acute stress that harms kids’ and parents’ health in the short term and may reverberate far into the future.

2. A looming eviction crisis

With many families in a precarious financial state, there is an impending wave of potential evictions in the months ahead. As of mid-July, just over one-third of adults with children in renter households were highly confident that they would be able to pay their next month’s rent.[15] This is unsurprising given that over half of families have experienced a loss of employment income since the start of the pandemic.

But even before COVID-19, affordable housing was already out of reach for many families. Three of every 10 children in Washington were living in housing cost-burdened households – meaning they spend 30% or more of their monthly income on housing expenses, according to the most recent data from 2018.[16] For children in families with lower incomes (incomes at or below 200% of the Federal Poverty Level), nearly two-thirds were housing burdened.[17] Families who spend such large shares of their incomes on housing may have to make critical tradeoffs to meet other basic needs, such as food and health care.

Although Washington state extended a moratorium on evictions through December 2020,[18] it does not guarantee that families will be safe from eviction in the long-term. Renters will have to pay back missed and current rent once the moratorium is lifted.[19] Those unable to pay rent will be particularly vulnerable to an eviction – and this is especially true of households with kids. Renter households with children are nearly three times more likely to receive an eviction notice, according to a study of evictions in Milwaukee.[20] This will inevitably have a greater impact on BIPOC families, who are more likely to be renters due to decades of harmful housing, economic development, and financial policies that have excluded people of color – especially Black people – from homeownership and wealth building.[21]

Lessons from the Great Recession can inform policies and decisions to mitigate the impact of housing disruptions for families and children. Five years into the Great Recession, nearly eight million children across the country were affected by the long, drawn-out foreclosure crisis.[22] Housing losses caused traumatic, widespread harm to children with cascading impacts on their education, physical health, mental health, and future earnings.[23] Children who receive housing subsidies experience lower rates of incarceration and have higher incomes as adults.[24] Housing subsidies and other protections can help provide stability for children now and in the future and address the potentially long-term housing crisis ahead.

3. Rising food insecurity

It was evident early on that Washington was facing a rapidly escalating food security crisis as the pandemic progressed. The number of Washingtonians considered food insecure (households that struggle to eat three meals per day due to a lack of money or other resources) nearly doubled from 850,000 individuals before the pandemic to 1.6 million by May 2020, and may grow to 2.2 million between now and December.[25] While these estimates do not delineate the number of children affected, data prior to COVID-19 show that U.S. households with children, especially those headed by single parents, Black, Latinx, and low-income individuals, are among the most likely to be food insecure.[26] One in every six kids in Washington was already living in a household that had trouble putting food on the table.[27]

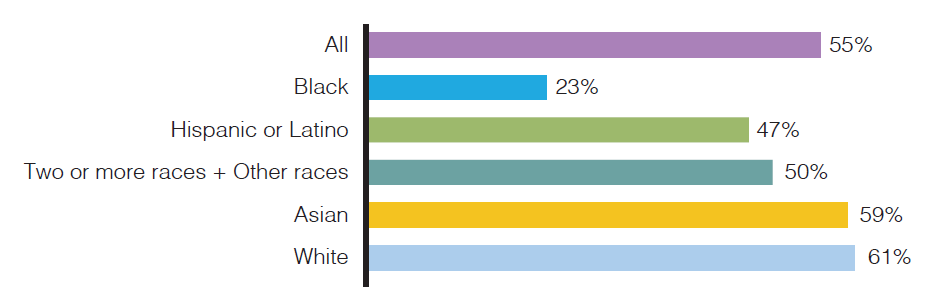

All families in Washington have experienced heightened food challenges since the start of COVID-19, and the challenges are particularly severe for Black and Latinx families, according to data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey. When the Household Pulse Survey first began in April, 44% of Black adults with children had enough of the types of food they wanted. By July, that had declined to only 23%. Fewer than half of Latinx adults with children had enough of the types of food they wanted during both periods.

Black and Latinx families are the least likely to have enough of the types of food they want

Percent of adults with children in Washington state that had enough of the types of food wanted, July 2020

As with many of the other impacts of COVID-19 on children and families, hunger and food insecurity are worsened by the loss of employment income by parents and caregivers. They are also increased by school closures; many children from families with lower incomes rely on school meals for regular access to healthy food. In response to the growing need, SNAP and the new Pandemic EBT (a program to provide additional one-time cash assistance to families of K-12 children who are eligible for free or reduced-price meal programs to buy additional groceries) have been helping families keep food on the table. The continuation and expansion of these two programs will be necessary to continue alleviating food insecurity going forward. During the Great Recession, SNAP responded better to household need than any other safety net program. At the peak of program participation in 2011, one in seven Americans relied on SNAP for food assistance. Even though the recession had ended, severe financial hardship and a slow economic recovery left many still reeling from the downturn.[28] For children, in particular, SNAP offered critical protections that also support better health, school performance, and positive long-term economic self-sufficiency.[29]

Jiji Jally, Marshallese Women’s Association, Auburn

As a citizen of the Marshall Islands in the western Pacific, Jiji may live, work and study in the U.S. due to a diplomatic arrangement, called a Compact of Free Association (COFA), between the two governments. Washington state is home to the largest COFA migrant community in the contiguous U.S., and its members disproportionately work in essential jobs with some of the highest exposures to COVID-19, such as nursing homes and meatpacking plants.COFA migrants, who also hail from Palau and the Federated States of Micronesia, are ineligible for many forms of public assistance (e.g. SNAP, Medicaid), but they can qualify for a program much like SNAP called State Food Assistance (SFA).

During the Great Recession, state lawmakers cut SFA severely, and did not restore it until 2015. Washington state’s COFA community comprises thousands of adults and children on both sides of the Cascades.

“Our people come to the U.S. and start from the bottom, work at the lowest wages, bunch up together, and together they try,” says Jiji. But the lowest wages don’t put enough food on the table. State Food Assistance helps.

“When you buy food for your family when you don’t have food stamps, you get rice and meat, flour, sugar. When you do, you get fruits, vegetables: the kinds of things that all kids deserve.”

4. A child care system at the brink of collapse

The impact of coronavirus on child care has been widespread across the state for both families and providers. For parents, many began working from home and many others lost employment altogether. Some child care providers had to close temporarily, some were only serving children of essential workers, and others have been forced to close permanently. Two-fifths of child care providers surveyed, half of which are minority-owned businesses, are certain they will close permanently without additional public assistance, according to a recent study by the National Association for the Education of Young Children.[30] Here in Washington state, more than 1,000 programs have closed and many have furloughed or laid off staff because enrollment in child care has significantly declined.[31]

But the challenge of accessible, affordable, and high-quality child care in Washington is not one that emerged out of the pandemic; the state was already deep in a crisis in which the cost of child care rivaled tuition and rent.[32] This was in part due to austerity-based budget and policy decisions made during the Great Recession aimed at addressing state budget shortfalls. In an attempt to balance the budget, legislators made devastating cuts rather than raising progressive revenue for critical community investments. Lawmakers consistently underinvested in this critical system when they could have instead bolstered support for parents by increasing the eligibility threshold for the Working Connections Child Care program, so that parents could maintain child care as they gained employment and their wages increased. They could have also supported child care providers by raising reimbursement rates to help them maintain financial viability.[33] Instead, from 2009 to 2011, cuts to public spending in Washington state resulted in approximately 7,000 parents losing crucial child care support.[34]

The longer-term implications of child care closures have important consequences for children and families and the economy overall. Parents need access to child care to work, and children need safe, nurturing environments to learn and grow. Research has consistently found that investments in early childhood education can lead to better outcomes later in life and are predictors for educational attainment, employment, and earnings as an adult.[35]

Luc Jasmin III, owner, Parkview Early Learning Center, Spokane

In 2011, state officials cut funding for the Child Care Career and Wage Ladder, which offered income and educational support to early childhood professionals dedicated to the field. As a result, Luc left the field of early childhood education for K-12.

“The individual impact of the cuts that took place back during the Great Recession was a great flight out of early learning,” he says. “A lot of those teachers who left were those who looked like the communities they served: teachers of color, teachers from diverse backgrounds.”

Now that job losses are again hurting the child care job sector, Luc fears that “the kids hurt most” by the lessening of that diverse pool of qualified educators, he says, “are the kids of color and those furthest from opportunity.”

“We need to be very smart about where we put our investments right now. It’s imperative to make sure we’re keeping programs open—imperative to make sure those communities of color are able to continue their care.”

“Let’s be honest about where we are compared to the rest of the world: if we really love America, we need to be invested in our youth, because we know our youth is our future. I’m really looking at where our kids are at; we need to compete and we need to preserve our democracy.”

5. Barriers to participation in online education and COVID-related learning loss

COVID-19 has shifted the educational lives of children across our state – upending where and how kids learn and undermining their access to the instruction and supportive services they need to thrive. Children and their families managed an abrupt transition to remote learning following necessary school closures in response to the pandemic. Plans to reopen many K-12 schools and early learning facilities across the state remain uncertain.

During this period, parents and caregivers (in tandem with educators) have worked hard to adapt and support their kids to maintain some level of access to instruction and other supports[36] – even as they’ve continued to balance the demands of their own jobs. Despite these efforts, many children face barriers that make meaningful participation in online learning more difficult. Kids with disabilities, in families without stable housing, those whose parents speak limited English, and others may not have access to the services (or physical workspace) they need to be successful in a remote setting.[37]

More than 1 in 10 adults in households with children in public or private school report they do not have a computer or other device reliably available for educational purposes.[38] Household Pulse Survey data show that BIPOC kids have even less access to the devices they need. This is the result of structural and institutional racism, including that disproportionately Black and brown schools have been historically deprived of public investment and are less likely to have the resources they need to supply student laptops or other equipment.[39] BIPOC kids and families are also less likely to be connected to the high-speed internet that’s necessary to maintain a reliable connection for virtual learning. American Community Survey data show that American Indian and Alaska Native, Latinx, and Black people in Washington state were steeply impacted by the digital divide even prior to COVID-19. Indigenous people living on tribal land, especially, are vastly under-served by broadband internet service.[40]

BIPOC families face greater barriers to the reliable technology required for remote learning

Percent of households in Washington state with a broadband internet subscription, 2018

Researchers predict that significant learning losses from prolonged COVID-19-related school closures are likely to occur. Drawing from the evidence on summer learning loss, one national analysis predicts that the average student began the 2021 school year having lost as much as one-third of the expected progress from the previous year in reading and half of the expected progress in math.[41] Many students and their families have experienced trauma during the pandemic (heightened economic stress, health impacts, etc.) that will further exacerbate learning losses. Other research estimates that these learning losses will have long-term economic consequences, reducing future earnings by $1,337 per year per student.[42]

State lawmakers can limit these losses by expanding access to broadband and other necessary technology as well as strengthening targeted supports for students with disabilities, dual-language learners, and others who face particular barriers to remote learning. However, doing so will first require them to reject the short-sighted cuts approach they chose in the wake of the Great Recession. The deep cuts lawmakers made then to Washington state’s education system undermined kids’ and families’ access to high-quality early learning, K-12, and higher education. Between 2009 and 2011, the number of teachers in classrooms shrank by nearly 3,000 (even as the number of K-12 students increased by 12,135), the average cost to attend college rose by 94% for four-year institutions and 54% at community and technical colleges, and tens of thousands of students did not receive the financial aid they were eligible for because of the state’s failure to invest.[43]

With the future of Washington’s kids at stake, state lawmakers cannot afford to repeat these grave mistakes. Instead, they must choose to bolster investments in education and strengthen the supports kids need to learn, grow, and weather the challenges posed by the COVID-19 crisis.

Lessons in Collaboration

Starting in March 2020, Whatcom County officials partnered with local districts to repurpose shut-down school facilities to meet emerging health, hunger, and child care needs. Public and private entities worked together to ensure that the children of essential workers could sustain their learning and care experiences while their parents were on the job. They acted as distribution points for essential supplies and personal protective equipment. With the help of school personnel, they distributed critically needed meals. School nursing staff performed health checks at local child care facilities.

Strong inter-agency collaboration, combined with expertise in the administration of birth-to-five and before- and afterschool care, helped ensure the success of these efforts, says Kristi Dominguez, executive director of learning and teaching at Bellingham Public Schools.

“What carried us into this is we had developed lots of strong partnerships prior. We also developed fast partnerships early. You have to invest in those partnerships,” said Dominguez, who was tasked with the formation of this countywide, unified response.

Dominguez had worked with the state Department of Children, Youth & Families to license many of her districts’ buildings for child care.

“As a coalition, we came together and asked ourselves: What do we have?” she said. “School districts have space. Therefore, we can bring child care providers in to be with kids. We have wi-fi; therefore we can offer access to technology; we have health staff, therefore we can go out and do health checks.”

Pooling resources effectively, she says, “has raised the whole question of ‘When does learning happen for a child?’ The birth-to-five system can’t do it alone; they need the resources that come from K-12. And the collective vision we share, that family is the first teacher: this experience has really brought that forward.”

Recommendations

To protect families from further harm during the pandemic, state and federal lawmakers should:

Help families meet their basic needs by strengthening vital health, income, housing, and food supports by:

- Preserving and expanding access to health care: Eliminating health coverage for any child would weaken our public health system and further entrench racial and ethnic disparities that are unduly exposing BIPOC families to COVID-19. At the state level, Washington lawmakers must preserve the Children’s Health Program and embrace health care innovations – such as dental therapists – to ensure children in immigrant communities and communities of color can access the care they need. At the federal level, Congress should restore Medicaid eligibility to thousands of COFA migrant families.

- Providing direct cash assistance to families most impacted by the COVID-19 crisis: Low-barrier, flexible cash assistance to families with low incomes is one of the most effective ways to support the dignity and well-being of kids and families. To support Washingtonians to weather the COVID-19 crisis, lawmakers should create an immediate state Recovery Rebate payment through federal Coronavirus, Aid, Relief, and Economic Secruity (CARES) Act funding. They should also invest in a permanent Working Families Tax Credit, our state’s version of the highly successful federal Earned Income Tax Credit program, and extend its support to caregivers, childless adults, and immigrants who file taxes with an Individual Tax Identification Number (ITIN).xliIn addition to enacting these new benefits, lawmakers must reduce barriers to existing cash assistance programs like WorkFirst/TANF by easing strict program requirements that make it difficult for families to access support.

- Expanding support to families regardless of immigration status: Because of discriminatory eligibility criteria, undocumented immigrants have been excluded from federal relief like the stimulus payments provided through the CARES Act and routinely barred from most public support programs (like TANF, SNAP, and unemployment insurance). To fill this critical gap, state leaders should immediately bolster investment in a Washington Immigrant Relief Fund so that immigrant families can access support during the crisis. Over the long term, they should create an unemployment insurance system that is available to people who are undocumented so that job loss does not jeopardize immigrant families’ health and safety.

- Preventing evictions and supporting families to pay rent: State policymakers must ensure that Washington’s state-level eviction moratorium remains in place for the duration of the public health and economic crisis – which may last beyond the end of this year. They must also provide robust rental assistance so that families do not face homelessness when accumulated back rent eventually comes due.

- Resourcing food assistance and child nutrition programs: State lawmakers can ensure children and families have enough to eat by making ongoing investments in Washington’s Fruit and Vegetable Incentives Program, which supports families receiving SNAP to purchase nutritious food. State lawmakers can also provide dedicated funds to support child nutrition programs, which have been hard-hit with higher costs for labor, supplies, and staffing during the pandemic.

Protect and strengthen early learning by:

- Supporting child care small businesses by raising Working Connections Child Care reimbursement rates (so that providers who care for kids with low family incomes can afford to stay in business), and make targeted investments that support BIPOC providers and providers whose first language is not English to re-open and remain open as the crisis continues. They should ensure child care workers have access to personal protective equipment, health coverage, and adequate compensation, so that they can safely continue their essential work.

- Supporting families to access quality child care by ensuring that families do not lose access to child care because they’ve recently received enhanced unemployment payments, hazard pay, or overtime pay. Lawmakers should expand eligibility for subsidy through Working Connections Child Care, cap child care expenses at 7% of household income, and increase access to free preschool through the Early Childhood Education and Assistance Program.

Support and resource K-12 students, families, and schools by:

- Supporting students to make up learning losses, with targeted support for students with disabilities, English language learners, BIPOC children, and those in families with low incomes.

- Eliminating barriers to technology by using federal aid and state investment to connect suburban and rural Washington communities and tribal nations with broadband internet, and deploy digital navigators to help students, workers, and elders overcome barriers to technology with professional support.

Raise progressive revenue and fix our state’s upside-down tax code:

Washington needs dependable sources of revenue to both address our state budget shortfall and generate enough resources to invest in kids and families. This starts with cleaning up our worst-in-the-nation tax code, in which low- and middle-income families pay as much as six times more in taxes as a share of their incomes than the wealthiest.[44] State lawmakers should end wasteful tax breaks on the ultra-wealthy – such as the one on capital gains (profits made from the sale of high-end financial assets) – and repeal harmful limits on revenue-raising to help flip our tax code right-side up. Cleaning up our tax code and raising revenue equitably will be an important first step to generating the necessary resources to invest in the well-being of children and families.

Finally, federal lawmakers must pass a robust COVID-19 relief package:

Congress must pass a new relief package that includes meaningful support for the urgent needs of children, families, schools, and child care providers. This should include robust aid to state and local governments and tribal nations, an extension of the Unemployment Insurance expansions that were originally a part of the federal CARES Act, additional stimulus payments, boosting SNAP, extending Pandemic EBT, investing in TANF, and more.

Authors: Liz Olson, Jennifer Tran, Adam Hyla E. Holdorf.

Thank you to Jiji Jally, Luc Jasmin III, Kristi Dominguez, and David Beard for their assistance with this report.

This research was funded by The Annie E. Casey Foundation, Inc., and we thank them for their support; however, the findings and conclusions presented in this report are those of the authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Foundation.

Find hundreds of indicators of child wellbeing at the state, county and national levels at the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s .

[1] Quianta Moore and Christopher Greeley, Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, June 2020.

[2] Washington State Department of Health, as of October 12, 2020.

[3] Washington State Budget & Policy Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey, Phase 2, Employment Table 1. Experienced and Expected Loss of Employment Income by Select Characteristics, Washington state. These figures reflect the average of data collected August 19-September 28, 2020. Fifty percent of adults in households with children report employment income losses, while 45% of adults overall report such losses.

[4] Danielle Wiener-Bronner, CNN.com, August 5, 2020.

[5] Scott Horsley, NPR, August 17, 2020.

[6] J. Craig Shearman, National Retail Federation, July 15, 2020.

[7] Washington State Budget & Policy Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey, Phase 2, Employment Table 1. Experienced and Expected Loss of Employment Income by Select Characteristics, Washington state. These figures reflect the average of data collected August 19-September 28, 2020.

[8] Elise Gould, Daniel Perez, and Valerie Wilson, Economic Policy Institute, August 2020

[9] Elise Gould and Valerie Wilson, Economic Policy Institute, June 2020.

[10] Danyelle Solomon, Connor Maxwell, and Abril Castro, Center for American Progress, August 2020.

[11] Washington State Department of Social and Health Services, preliminary WorkFirst/TANF and SFA caseload data, September 2020.

[12] Washington State Department of Social and Health Services, preliminary SNAP and FAP caseload data, September 2020.

[13] Julie Watts and Liz Olson, Washington State Budget & Policy Center, January 2020.

[14] The National Academy of Sciences, 2019.

[15] Washington State Budget & Policy Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey, Phase 1, Housing Table 2b. Confidence in Ability to Make Next Month’s Payment for Renter-Occupied Housing Units, Washington state, Week 12.

[16] KIDS COUNT Data Center, 2018.

[17] KIDS COUNT Data Center, 2018.

[18] Joseph O’Sullivan, Seattle Times, October 8, 2020.

[19] Northwest Justice Project,

[20] Matthew Desmond, Weihua An, Richelle Winkler, and Thomas Ferriss, Social Forces 92(1) 303–327, September 2013.

[21] Pedro da Costa, Economic Policy Institute, April 2019.

[22] Julia B. Isaacs, The Brookings Institution, April 2012.

[23] The Aspen Institute’s Expanding Prosperity Impact Collaborative, May 2019.

[24] Emily Peiffer, Housing Matters, Urban Institute, July 2018; Fredrik Andersson, et al, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 22721, September 2018.

[25] Estimate provided by Northwest Harvest in May 2020. The estimate is based on needs assessment by Northwest Harvest, Food Lifeline, Second Harvest and Washington State Department of Agriculture based on the number of people that are food insecure, the number of children that are eligible for free and reduced price meals, the percentage of seniors living in poverty, and the number of unemployment assistance applications.

[26] Economic Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture, .

[27] Northwest Harvest,

[28] Ben Senauer, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, August 2012.

[29] Steven Carlson, Dottie Rosenbaum, Brynne Keith-Jennings, and Catlin Nchako, Center on Budget & Policy Priorities, September 2016.

[30] National Association for the Education of Young Children, July 2020.

[31] Nina Shapiro, Seattle Times, August 9, 2020; State of Washington Department of Commerce, July 2020.

[32] Liz Olson, Washington State Budget & Policy Center, April 2019.

[33] Ruth Kagi, Seattle Times, July 14, 2020.

[34] Kim Justice and Andy Nicholas, Washington State Budget & Policy Center, December 2011.

[35] Ann O’Leary, Washington Center for Equitable Growth, September 2014.

[36] Washington State Budget & Policy Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey, Phase 1, Education Table 1. Time Spent in Last Week on Home Based Education for Households with Children in School, by Select Characteristics. These data show that nationally, parents and caretakers are dedicating a significant number of hours per week (more than 11 during the school year and more than four during the summer) to teaching activities.

[37] Natalie Spievack and Megan Gallagher, Urban Institute, June 2020.

[38] Washington State Budget & Policy Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey, Phase 1, Education Table 3. Computer and Internet Availability in Households with Children in Public or Private School, by Select Characteristics, Washington state. The authors considered respondents to have reliable access to a computer if they answered that such technology is “always” or “usually” available for educational purposes.

[39] EdBuild, February 2019.

[40] Hansi Lo Wang, NPR, December 2018.

[41] Megan Kuhfeld, James Soland, Beth Tarasawa, Angela Johnson, Erik Ruzek, and Jing Liu, Annenberg Institute at Brown University, EdWorkingPaper No. 20-226, May 2020.

[42] George Psacharopoulos, Harry Patrinos, Victoria Collis, and Emiliana Vegas, The Brookings Institution, April 2020.

[43] Kim Justice and Andy Nicholas, Washington State Budget & Policy Center, December 2011.

[44] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, 2018.