About this brief:

This brief is a follow up to our 2020 product, “What Washington’s kids need to weather the challenges of the COVID-19 crisis and beyond.” Recent U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse data and stories from community members across the state show how the pandemic continues to affect kids and families in the areas of housing, nutrition, health care, and education. Lawmakers need to build on the success of the last legislative session to further investments in the lifelong health and wellbeing of kids and families. In this brief, we call on state and federal lawmakers to use a health equity lens to enact budgets and policies that promote the long-term health of children in Washington.

In the 2021 legislative session, policymakers took bold action to protect Washington’s kids and families from the impacts of COVID-19 and lay the groundwork for their long-term health. However, nearly two years after its onset, the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated economic fallout persist in Washington state and continue to touch nearly every aspect of our lives.

The dangerous acceleration of the Delta variant in recent months and COVID-19 outbreaks in schools are a stark reminder that children and young people are not immune to the harmful effects of the pandemic. In addition to the increase in the number of children hospitalized with COVID-19, kids are shouldering immense hardship and stress associated with the crisis. And this is all on top of the challenges and barriers caused by long-standing racist policies and practices that prevent some children from the opportunities they deserve. Recent data from the U.S. Census Bureau and other studies show that children – especially those in Black, Latinx, and other families of color – have experienced worsened mental health, food insecurity, housing instability, lack of health care, and lack of digital access for remote learning.

Our health is a product not only of our genes and individual health choices, but also the environment in which we are born, live, learn, and play. These factors are collectively known as “social determinants of health.”

A child’s living environment, access to quality education and health care, socioeconomic status, and their family and community shape their likelihood of having clean air to breathe, a job with a living wage and benefits, money to pay for nutritious food, and someone to lean on for their emotional and mental well-being. Researchers have found that the social determinants of health account for fully 70% of our health.

The social determinants of health have a big effect on Washingtonians’ well-being and are determined in part by decisions about fiscal policy. So, state and federal lawmakers have a responsibility to consider the impact that policy decisions about the distribution of money and resources will have on our state’s public health. The World Health Organization states that the unequal distribution of power, money, and resources at the global, national, and local levels are responsible for the health inequities we see. [1] To ensure the health and well-being of every child, elected leaders must take continued action to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 and foster the social, economic, and political conditions that provide every child with the resources they need.

State lawmakers took bold action to invest in kids in the last legislative session

Policymakers made great strides over the last year to provide relief to the kids and families most impacted by the pandemic and invest in critical supports that have been underfunded for decades. They did so in response to the leadership and organizing work of communities across Washington. These investments will help all kids, but will be particularly beneficial to Black, Indigenous, and kids of color, who face additional barriers to opportunity and success because of generations of discriminatory policy and distribution of public resources. Policies to advance opportunity and public health enacted last session include:

Early learning: The Fair Start for Kids Act (FSKA) expanded access and affordability of early learning and child care programs, primarily through changes to the Working Connections Child Care (WCCC) and the Early Childhood Assistance and Education Program (ECEAP) [2] . FSKA expands eligibility for the programs, reduces families’ share of the cost for child care, and increases the amount paid to child care centers and early learning teachers. As mentioned above, education – particularly early education – provides a strong foundation for long-term health.

Cash assistance: The Working Families Tax Credit (WFTC), $340 million for the Washington Immigrant Relief Fund, and 15 percent increase to Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) will provide significant financial relief through direct cash assistance to families with low incomes [3] . This will give adults freedom to purchase basic necessities and pay for living expenses that keep themselves and their children safe and healthy.

Housing: Extension of the eviction moratorium through October of 2021, over $650 million in rental assistance, and nearly $200 million for foreclosure prevention helped hundreds of thousands of families to stay in their homes. [4]

Progressive revenue: The capital gains tax will generate over $500 million in progressive revenue to fund early learning programs, child care, and schools. [5]

Deep hardship persists among Washington’s families with kids, especially among Black, Latinx, and other families of color

While young kids have the lowest COVID-19 fatality rate, they have nonetheless experienced harm to their physical and mental health. Since the onset of the pandemic, child advocates and researchers have raised concerns about the effect of growing up in a time of global uncertainty and instability on children’s and adolescent’s mental well-being. National studies show that the combination of school closures, social isolation, and decreased physical activity have led to increased anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation among kids and teens [6,7] . And children in foster care are four times more likely than other children to attempt to take their own lives. [8]

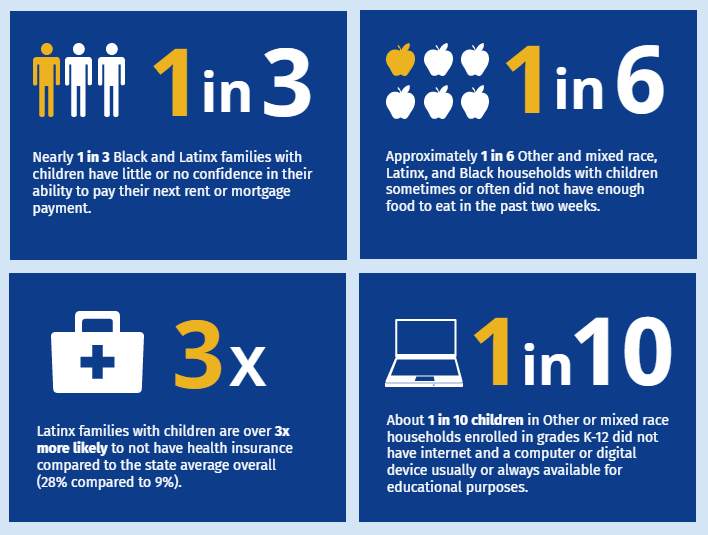

The U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey has been collecting data biweekly to see how families are faring during the pandemic. Data from April to August of 2021 shows that in many ways, families in Washington were doing better during that period than they were when the pandemic began. However, deep hardship persists among many Washingtonian families, with Black, Latinx, and other families of color experiencing disproportionate harm from the ongoing crisis, including having been excluded from opportunities to recover.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey data from April 14 to Aug 2, 2021, in Washington [9] :

Policy recommendations to ensure the health of kids in our state

Policymakers must build on the successes of the last legislative session to deliver on the promise of an equitable recovery and strengthen the health of our communities. The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the importance of housing, education, health care, and cash assistance for the health of all people.

These investments are particularly important for children who are still growing and need more support and stability to facilitate their development. A recent national study of state spending from 2010 to 2017 found that greater spending on support for Washington people and families such as cash, housing, child care assistance, a refundable Earned Income Tax Credit, and healthcare is associated with reduced child abuse and fatality [10] . These findings reveal the significant benefit these programs have on children’s well-being. Elected officials at the state and federal level must support and strengthen these programs to lay the foundation for long-lasting health and well-being for all kids in Washington. With approximately $1 billion in remaining American Rescue Plan Act funds, Washington state can leverage some of these resources to continue investing in children and families.

Policymakers must build on the successes of the last legislative session to deliver on the promise of an equitable recovery and strengthen the health of our communities. The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the importance of housing, education, health care, and cash assistance for the health of all people.

1. Prioritize direct cash assistance

Lawmakers should continue to prioritize direct cash assistance to families most impacted by the COVID-19 crisis. Low-barrier, flexible cash assistance to families with low incomes is one of the most effective ways to provide stability and promote the health of kids and families. Congress should permanently expand improvements to the Child Tax Credit (CTC) enacted as part of the American Rescue Plan Act (ARP), so that this more effective CTC remains available to children and families beyond 2022. Approximately 1.3 million kids in Washington state are estimated to benefit from the policy’s expansion, meaning monthly payments of up to $250 to $300 per child for qualifying households (about $430 on average per household) [11] . The Child Tax Credit has helped families across the country pay for food, rent, essential bills, and other basic needs. Just a month and a half after the first Child Tax Credit payment was issued, the number of adults with children who said they didn’t have enough to eat dropped by almost one-third [12] . Additionally, lawmakers must continue to reduce barriers to existing state cash assistance programs that make it difficult for families to access support.

2. Continue to enact bold, equitable revenue reforms to generate sustainable resources to invest in the wellbeing of children long term

Creating opportunities for children and families to lead healthier lives requires long-term, sustained investments even long after the pandemic ends. To generate resources, lawmakers will need to continue cleaning up our upside-down tax code, which makes low- and middle-income families in the state pay a far greater share of their incomes in state and local taxes than the wealthy pay – as much as six times more, in some cases [13] . In the 2021 legislative session, because lawmakers enacted a new excise tax on extraordinary stock profits (capital gains), there will be resources to fund the Fair Start for Kids Act, a historic new law that will make high-quality child care, preschool, and other early learning services more affordable and accessible to parents with young children [14] . Continuing to enact new taxes on Washington’s wealthiest residents and large, profitable corporations would help turn the tax code right-side up while providing our state with more revenue invests in the programs and policies that can ensure a brighter and healthier future for Washington’s children.

3. Invest in child nutrition programs

Both state and federal lawmakers can promote the health of children and families by ensuring they have enough to eat. Every five years, Congress reauthorizes key child nutrition programs through the Child Nutrition Reauthorization. It is an opportunity to strengthen and expand critical nutrition programs including the National School Lunch Program, School Breakfast Program, Child and Adult Care Food Program, Afterschool Meal Program, WIC (the Women’s Infants and Children supplemental nutrition program), and more. These programs provide meals for more than 20 million children across the nation and are especially important for children in families with low incomes. Through the reauthorization process, Congress can further ensure that kids and families do not go hungry by extending the WIC certification period to two years, extending program eligibility for children to six years, and extending postpartum eligibility to two years for all mothers. They can also lower the eligibility requirements for a community to participate and expand the reach of summer meal programs to underserved areas. Additionally, they can expand and make summer EBT permanent so kids can access food when school is out at other times of the year. [15-17]

In Washington state, lawmakers should invest an additional $59 million for the Department of Agriculture to continue the Farm to Families Food Box program. This will provide fresh, local produce to Washingtonians and alleviate food insecurity among kids and families.

HUNGER: Racial disparities worsened

Despite initial fears that household hunger would spike during the pandemic, the overall hunger rate was stable. But inequality did grow, said Claire Lane, director of the statewide Anti-Hunger & Nutrition Coalition: Black, Latinx, and other households of color became hungrier relative to White households.

“Like most every other metric related to COVID, the pandemic revealed and made worse the existing racial disparities and economic disparities in our communities,” said Lane.

Longstanding barriers to food security take four forms, said Christina Wong of the anti-hunger agency Northwest Harvest. People of color are more likely to work frontline jobs that are also lower in wages and more subject to layoffs due to illness or other family obligations, with no or limited benefits to help. These households are more likely to encounter logistical barriers to getting services at school meal distribution sites and food banks during operating hours. And while a range of federal COVID relief measures, such as pandemic EBT and the child tax credit, alleviated hunger for many families, immigrant families had more limited access to this aid. And immigrant families face a clear deterrent to using public benefits or providing an ID at a charity: the lingering fear of the Trump administration’s public charge rule, which threatened to block the path to legal immigration for anyone who used some form of aid.

In response, Wong said, some community-based relief agencies have found ways of getting food to hungry families using methods informed by these barriers. These efforts are “helping BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) families who are not otherwise accessing established food banks” by lifting any monthly bars on the number of visits and not requiring an ID. As a result, “They believe they have been successful at being trusted by their communities.”

Public officials are supporting these efforts: This fall, the Washington State Department of Agriculture is launching a $45 million effort to put locally grown produce into food boxes that serve BIPOC and other historically marginalized families. Nonprofit organizations, like Feeding Feasible Feasts, a Pierce County organization that delivers 3,000 boxes of food to families whose children are enrolled in Head Start, can select food providers and family farms and arrange for boxes or bags of food that best suit their clients.

“Farmers want to know that the food they’re growing gets to people who need it,” said Katie Rains, food policy advisor to the director of the Department of Agriculture. “One of their incentives is to have stable revenues and market access, and many of them donate surplus produce already.”

This state-level initiative is only partly compensating for a larger, more robust federal program supported by CARES Act, FEMA, and state emergency funding, which delivered at least 1.5 million pounds of food to Washington’s families each week until early summer 2021. That funding “disappeared overnight,” said Rains, and the Department of Agriculture is only able to partially restore that food volume, she said. To fully restore the food program, the Department is asking state lawmakers to increase funding for food boxes during the 2022 legislative session by $59 million.

4. Expand and include support to families regardless of immigration status

All kids – regardless of their families’ immigration status – deserve the basic security of knowing they’ll have food to eat, a roof over their heads, and access to health care when they’re sick. The pandemic has brought unique harm to children in immigrant families, many of whom have been excluded from federal relief like the stimulus payments provided through the CARES Act and routinely barred from most public support programs (like TANF, SNAP, and unemployment insurance) because of discriminatory eligibility criteria. At the federal level, Congress should pass the , which would lift the five-year waiting period for immigrants with legal status to apply for SNAP, Medicaid, and other benefits. The five-year exclusion period is a racist policy that prevents millions of immigrants from receiving basic needs such as food and health care, and threatens their health and safety.

In Washington state, lawmakers can build an unemployment insurance system that is available to people who are undocumented so that job loss does not jeopardize immigrant families’ health and safety. Additionally, Washington state must offer health care on the Washington Health Benefit Exchange that is at least comparable to Apple Health for all residents, regardless of immigration status. Individuals who lack health care coverage are less likely to receive service and necessary treatment, leading to poorer health. Removing barriers to health care for immigrants will reduce inequities in health care and health outcomes.

HEALTH CARE: “When parents don’t have care, all too often the kids don’t get it either.”

In the early months of the pandemic, Brenda Rodríguez López, executive director of Washington Immigrant Solidarity Network (WAISN), says her case management team was “getting thousands of calls: people who were very sick with COVID just staying home” because they had neither coverage nor the means to pay for care.

And in Washington’s immigrant communities, there’s a third barrier: the threat of state-sanctioned violence, in the form of arrest, detention and deportation.

This affects the whole family, says Catalina Velasquez, deputy director of WAISN: “You don’t need to be undocumented to live an undocumented life.” Because of the persistent concern for anti-immigrant action by public officials, when undocumented parents don’t have care, “all too often the kids, who are citizens, don’t get it either.”

Finally, because of the first three barriers, a fourth is created: In many immigrant communities lack of access “leads to a culture not just of not getting care, but of disdaining medical institutions,” says Velasquez, who shared she often has to encourage herself to go get the health care for which she’s insured. Even as a graduate of a prestigious university, with all her education, “knowing better doesn’t necessarily make the change.”

WAISN policy director Cariño Barragán Talancón coordinates the Health Equity (Igualdad en la Salud) Campaign, working to ensure that health coverage offered on the state’s Health Benefit Exchange, HealthPlanFinder, is available without regard to immigration status, and that cost-sharing measures make it affordable. “Growing up in my family, we never had access to health care,” says Barragán.

She’s not alone. With state legislation, Barragán’s past doesn’t have to be Washington’s future.

5. Eliminate educational inequities through investments in digital navigators

Lawmakers can help eliminate educational inequities by deploying digital navigators to help students and their caregivers overcome barriers to technology. State lawmakers should invest $10 million biannually in the Digital Navigators Program to provide culturally and linguistically appropriate technology support to students and families. It is not enough to have access to reliable internet and digital devices. Students and families must have support in navigating classes and resources online. Improving digital literacy will be critical in reducing educational inequities as schools continue to weather the pandemic. Setting up kids for success in school also paves the way for healthier futures. People with more education are more likely to engage in healthy behaviors, have less health problems, and live longer. [18,19] Having a high school diploma is also linked to being employed and earning higher wages, which provides necessary resources for health-related activities such as buying healthy food, paying for healthcare, and maintaining safe, stable housing.

TECH: Lack of digital access for remote learning

When schools in Washington closed and shifted to

online instruction in March 2020, education advocates like Sharonne Navas knew this would pose a critical problem.

Children’s access to a laptop or tablet, plus the internet access that enabled them to connect to their teachers, became a deciding factor in educational quality. And not all schools could put adequate equipment and an internet connection within reach of their families.

“The digital inequity was always there,” said Navas, founder and executive director of the Equity in Education Coalition of Washington. “COVID just exaggerated it.”

Navas’ organization began to connect digital specialists with parents who were troubleshooting their children’s technology problems. Her coalition employed nine staff who speak 15 languages and respond to inquiries from parents troubleshooting the tech needs of students who were attending school remotely. They do so by phone, Facebook chat, or web-based text chat. Families from any Washington school district can participate. In those communities where internet access was available, “What families needed most was digital literacy,” Navas said.

Lynda Hall, director of education policy and partnerships at Treehouse, which helps foster kids meet their educational goals, said she saw stark challenges to remote schooling in rural Washington where children and youth that experience foster care did not have reliable access to high-speed internet. Though some districts were able to offer mobile wi-fi hotspots staged on school buses, families in hilly regions of central and eastern Washington, where cellular service was weak, struggled to connect. These mobile hot spots were somewhat helpful—but they also highlighted how internet providers are poorly serving many communities.

The state is taking positive steps. In 2019 the Office of Broadband established a digital equity dashboard to gauge where high-speed internet access is unavailable now, in order to see which areas need it next. Navas said state officials will need data about families’ racial and ethnic background to extend broadband equitably.

Without equipment, information, or access, a substantial number of families surveyed by her organization during the pandemic did not hear from teachers for four or more months, Navas said. That indicates that the lack of access needs to be addressed, in the event of future situations where remote learning is necessary.

“I think one of the things we have to reckon with is that COVID isn’t going anywhere,” she said. “And most people are undereducated about what the digital divide is — it’s more than an inconvenience.”

6. Expand access to affordable housing and protect renters

Having a safe, stable place to call home is critical for children’s well-being. Children in families that are behind on rent, move multiple times in a single year, or have experienced homelessness are much more likely to have poor health. [20] However, the pandemic has exacerbated Washington’s affordable housing and homelessness crisis, with many families unable to pay rent and at risk of eviction. And decades of racist housing policies, such as redlining and discriminatory lending practices, continue to disproportionately block Black and brown families from homeownership and housing stability. Lawmakers should invest $400 million of remaining American Rescue Plan funds in building and preserving affordable housing so that families are not spending over one third of their income on housing costs. In addition, with the expiration of the eviction moratorium, many renters who fell behind on rent during the pandemic may be forced to leave their homes for failure to pay. Legislators must enact stronger tenant protections against rent-gouging so that families are not priced out of their homes and landlords are prevented from denying housing solely based on a tenant or family member’s previous incarceration.

HOUSING: “Vestiges of racism” put housing out of reach

Like many parts of the state, Skagit County in rural and suburban northwest Washington, has experienced rapidly escalating housing prices. Heavily dependent on rental housing, working families in the area also move between seasonal jobs in local fields and positions in food processing. Finding a home near a job has become a dire challenge, said Liz Jennings, director of community engagement at Community Action of Skagit County, which partners with other local aid agencies to offer housing referrals and resources in Spanish, Russian, and the Mixtec and Triqui languages of Mexico.

In response to the pandemic, the state and federal governments prohibited landlords from evicting tenants until the summer of 2021, though the governor continued a measure prohibiting evictions for lack of payment under some circumstances through October. Yet the families Jennings serves are experiencing “extraordinary rent increases” of 30 to 40 percent.

“In some cases, in response, we’re seeing forced self-eviction,” she said, as families have no choice but to leave their homes and hunt for more affordable options. But the lack of buildable land in the rural and suburban area, where single-family zoning is predominate, and other regulatory and financial barriers to cheaper development, means that “vestiges of racism” put secure housing out of reach for Latino workers and their families.

Maya Manus, advocacy & community engagement manager at the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle, sees some relief. Increased public aid “has been monumental” in helping individual families pay rent and utilities, she said. “Higher aid from state and federal sources “gives [families] the chance to pay for what they need: rent, utilities. With the child tax credit and the stimulus payments, these have been conversation changers.”

Authors: Tracy Yeung, Adam Hyla E. Holdorf, and Jennifer Tran

Design: Charlotte Linton

We gratefully acknowledge the following individuals for contributing their expertise and insights to this report:

- Brenda Rodriguez Lopez, Cariño Barragán Talancón and Catalina Velasquez, Washington Immigrant Solidarity Network

- Christina Wong, Northwest Harvest

- Claire Lane, Washington State Anti-Hunger & Nutrition Coalition

- Eleanor Bridge and Arik Korman, League of Education Voters

- Janet Varon, Northwest Health Law Advocates

- Katie Rains, Washington State Department of Agriculture

- Liz Jennings, Community Action of Skagit County

- Lynda Hall, Treehouse

- Maya Manus, Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle

- Michele Thomas and John Stovall, Washington Low Income Housing Alliance

- Sharonne Navas, Equity in Education Coalition

1. World Health Organization. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health – Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health.; 2008. Accessed October 4, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-IER-CSDH-08.1

2. New reforms bring balance and equity to state’s tax code and economy. Budget and Policy Center. Published July 7, 2021. Accessed October 4, 2021. https://budgetandpolicy.org/schmudget/new-reforms-bring-balance-and-equity-to-states-tax-code-and-economy/

3. Final budget proposal gets Washington state closer to an inclusive economy. Budget and Policy Center. Published April 24, 2021. Accessed October 4, 2021. https://budgetandpolicy.org/schmudget/final-budget-proposal-gets-washington-state-closer-to-an-inclusive-economy/

4. Nisba Gabobe. Washington’s 2021 Legislative Session Marks Historic Investment in Renter Relief. Sightline Institute. Published June 18, 2021. Accessed October 4, 2021. https://www.sightline.org/2021/06/18/washingtons-2021-legislative-session-marks-historic-investment-in-renter-relief/

5. Lawmakers act to balance state tax code by passing capital gains tax. Budget and Policy Center. Published April 25, 2021. Accessed October 4, 2021. https://budgetandpolicy.org/schmudget/lawmakers-act-to-balance-state-tax-code-by-passing-capital-gains-tax/

6. Lee SJ, Ward KP, Chang OD, Downing KM. Parenting activities and the transition to home-based education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2021;122:105585. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105585

7. Patrick SW, Henkhaus LE, Zickafoose JS, et al. Well-being of Parents and Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A National Survey. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):e2020016824. doi:10.1542/peds.2020-016824

8. Gurnon E. Suicide Looms Large in Minds of Many Foster Youth. The Imprint. Published September 28, 2020. Accessed October 4, 2021. https://imprintnews.org/childrens-mental-health/suicide-looms-large-minds-many-foster-youth/47755

9. Population Reference Bureau Analysis of U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey, 2021, January 6-March 29, 2021 and April 14-July 5, 2021.

10. Puls HT, Hall M, Anderst JD, Gurley T, Perrin J, Chung PJ. State Spending on Public Benefit Programs and Child Maltreatment. Pediatrics. Published online November 1, 2021. doi:10.1542/peds.2021-050685

11. U.S. Department of the Treasury. Average Child Tax Credit disbursement for households in Washington.

12. Sherman A, Marr C, Hingtgen S. Earnings Requirement Would Undermine Child Tax Credit’s Poverty-Reducing Impact While Doing Virtually Nothing to Boost Parents’ Employment. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Accessed October 4, 2021. https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/earnings-requirement-would-undermine-child-tax-credits-poverty-reducing-impact

13. ITEP. Washington: Who Pays? 6th Edition. ITEP. Accessed November 1, 2021. https://itep.org/washington/

14. Andy Nicholas, Liz Olson, Margaret Babayan. New reforms bring balance and equity to state’s tax code and economy. Washington State Budget & Policy Center. Published July 7, 2021. Accessed November 1, 2021. https://budgetandpolicy.org/schmudget/new-reforms-bring-balance-and-equity-to-states-tax-code-and-economy/

15. DeLauro RL. WIC Act of 2021.; 2021. Accessed November 1, 2021. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/2011

16. Young D. Summer Meals Act of 2021.; 2021. Accessed November 1, 2021. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/783/text

17. Murray P. Stop Child Hunger Act of 2021.; 2021. Accessed November 1, 2021. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/1831/cosponsors

18. Hahn RA, Truman BI. Education Improves Public Health and Promotes Health Equity. Int J Health Serv. 2015;45(4):657-678. doi:10.1177/0020731415585986

19. Kaplan R, Spittel M, David D. Population Health: Behavioral and Social Science Insights. Vol AHRQ Publication No. 15-0002. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, National Institutes of Health; 2015. Accessed October 4, 2021.

20. Sandel M, Sheward R, Ettinger de Cuba S, et al. Unstable Housing and Caregiver and Child Health in Renter Families. Pediatrics. 2018;141(2). doi:10.1542/peds.2017-2199

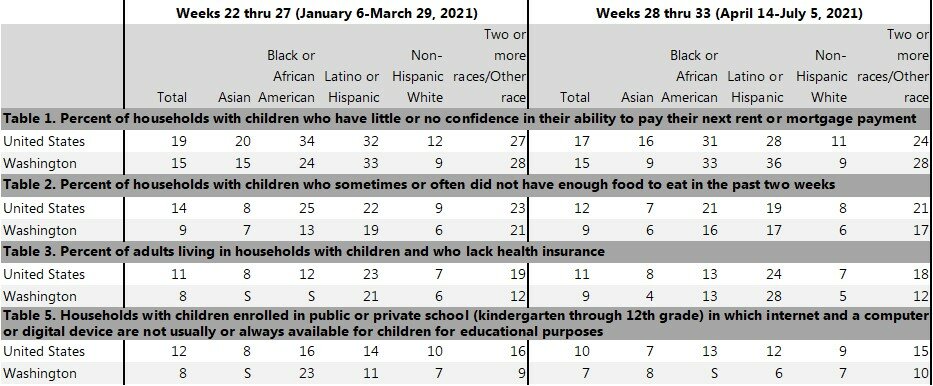

Appendix

Percentage of Households with Children Reporting Concerns During Pandemic

Source: Population Reference Bureau analysis of U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey, 2021, Jan 6-July 5, 2021 and Weeks 22 through 33.

Note: Only respondents who provided a valid response are included. Racial and ethnic groups represented in this table are not mutually exclusive. The white category includes only non-Hispanic white. The categories of African American, Asian, Two or More Races and other race include both Hispanic and non-Hispanic. Those in the Hispanic or Latino category include those identified as being of Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin. American Indian or Alaska Native, Pacific Islander and Native Hawaiian are included in the other race category.

S – Estimates suppressed when the effective sample size is less than 30 or the 90% confidence interval is greater than 30 percentage points or 1.3 times the estimate.

* For Phase 3 (which includes Jan 6, 2021-March 29, 2021), respondents were asked about internet and computer or digital device availability for students attending public, private, or home school. Beginning in Phase 3.1 (starting on April 12, 2021), respondents were only asked about internet and computer or digital device availability for students attending public or private school. Due to the change in who was eligible to answer questions about internet and computer or digital device availability for education purposes, estimates from Jan 6, 2021 through March 29, 2021 may not be comparable to those from April 12, 2021 or later.