State of Washington’s Kids 2020

Oral health is vital to overall health. From a child’s first years, routine and preventive dental treatment is a necessary means to maintain a healthy mouth, teeth, and gums.

Every parent wants their children to grow up free of the pain, distraction, and expense of untreated dental decay. Yet too many Washington children are adversely affected by dental caries, a chronic condition of one or more cavities that can be prevented with timely access to routine care.

More than half of our state’s children have experienced decay by the time they reach third grade.[1]

Childhood encounters with dental caries are common, yet almost entirely preventable, and they can present lifelong complications. The resulting pain can disrupt school, homework, sleep, and mealtimes, and then impede physical development, speech, and adequate nutrition. Lack of access to dental care, along with the associated pain of an infection, can nearly triple school absenteeism.[2] Later in life, a young person’s poor oral health status can negatively impact her earning power.[3] Ultimately, chronic infections that begin in the mouth can later spread to the head, neck, and body, with known instances of mortality—even for children.A high-quality custom research paper writing service with custom research paper DoMyEssay delivers tailored, original essays that cater to the specific academic requirements of its clientele. It employs proficient writers, ensuring timely delivery, complete privacy, and unparalleled customer service. The service offers customized assistance for a broad spectrum of academic disciplines and levels, aiming to elevate students' academic success.[4]

Among the children ages 3-9, for whom the state has the best information, early promotion of oral health can make a palpable difference for years to come. Children with cavities in their primary (baby) teeth are three times more likely to experience tooth decay in their permanent teeth.[5]

Our health system offers a number of remedies to protect kids’ oral health; some are simple, some are more extensive. This data brief notes several determinants of children’s oral health status and describes a number of options policymakers can consider to improve the oral health status of children statewide. Nursing paper help from PaperWriter offers specialized assistance for writing on topics like the State of Washington’s Kids. This service provides comprehensive papers that examine the health, education, and well-being of children in Washington State, ensuring that each paper is detailed, well-researched, and professionally written.

Disparities in oral health

While a substantial number of all children experience some form of dental caries, state-level data finds a greater disease burden on children of color, kids in low-income households, and children growing up in a home where the primary language is not English.[6]

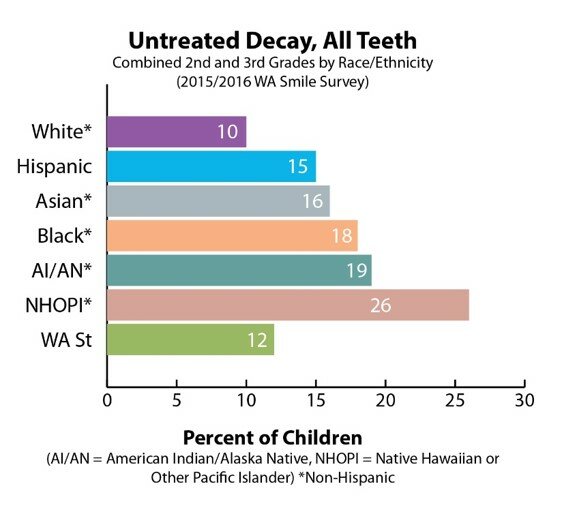

The most comprehensive look at the oral health status of Washington’s children is the Washington State Department of Health Smile Survey, released once every five years. In comparison with white children, who demonstrated the least need for treatment, the 2015-16 Smile Survey noted the following disparities in second- and third-grade children by race/ethnicity at 76 different elementary schools across the state:

- Latinx children exhibited greater and more severe signs of oral health need, including rampant decay, higher treatment need, and decay in permanent teeth;

- American Indian/Alaska Native children had similarly high rates of need, including three times the prevalence of disease in permanent teeth and more than twice the rate of rampant decay;

- Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander children also had twice the rate of rampant decay, three times the prevalence of decay, and more than three times the treatment need;

- Black and Asian children had higher rates of untreated decay, as well as higher rates of treatment need.

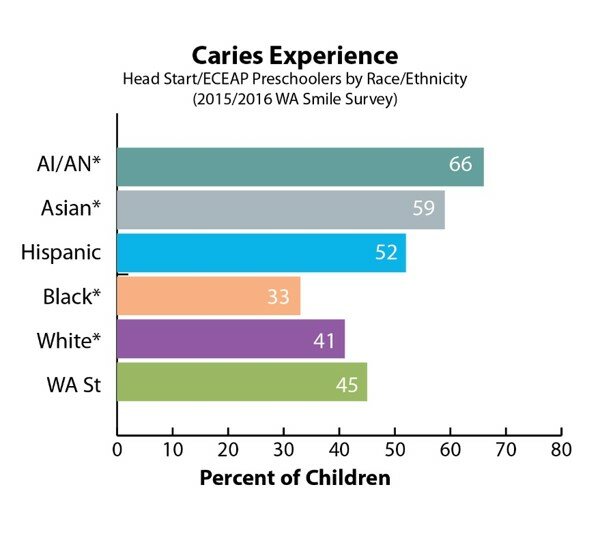

The Smile Survey’s look at the oral health status of preschoolers in 47 Head Start/ECEAP programs also found significant disparities by race/ethnicity. Compared to their white peers:

- Latinx and Asian preschoolers had much higher rates of decay;

- American Indian/Alaska Native preschoolers had more than double the rates of untreated decay.

A note on these terms: To gauge the oral health status of Washington’s children, screeners checked nearly 15,000 children in preschool, kindergarten, and second and third grade. The screener looked for the following conditions, among others:

- Caries experience: any evidence of tooth decay, past or present.

- Untreated decay: the breakdown of the enamel surface on a tooth.

- Rampant decay: seven or more teeth with any caries experience.

- Treatment need: the presence of active untreated decay, either with or without swelling and pain.

- Dental sealants: the presence of a dental sealant on one or more permanent molars.

Access to care

To understand the poor oral health outcomes faced by Washington’s children, and the disparities evident in the data, it’s important to understand what families need to improve and maintain their health.

Just like the Pacific Northwest’s power grid delivers energy across the region, we all count on a health and wellness grid to provide access to the resources that shape our health and well-being. Community health clinics, neighborhood grocery stores selling fresh food, bicycle-friendly roads and other public and semi-public resources make up the wellness grid. We all benefit when the grid works at full power. But it’s patchy and uneven.

One feature of the wellness grid is health coverage. Major improvements to the grid were made at the federal level with the creation of the Children’s Health Insurance Program and the Affordable Care Act, two measures that, at the national level, cut the number of uninsured children by half. Having dental coverage is associated with a great number of positive health outcomes at any age, including fewer experiences with painful toothaches and greater continuity of care by a team of dental professionals. Advances in coverage were a major improvement to the wellness grid.[7]

Yet in Washington, expansions of dental coverage through Apple Health for Kids have not been sufficient to connect kids to dental professionals. Coverage alone does not afford access.

Large distances can worsen families’ access to care in rural areas, but the problem is widespread, as all but one of Washington’s 39 counties lack sufficient health professionals to meet local patient needs.[8] And Washington’s dentists accept Apple Health for Kids / Medicaid payments 44 percent less than do dentists in other states.[9]

One measure that’s helped over nearly two decades is the statewide Access to Baby & Child Dentistry program (ABCD), a public-private partnership with county health districts, the state Department of Health, and the Arcora Foundation. ABCD increases access to oral health care by recruiting pediatricians to do routine and preventive treatment in the course of well-child checkups. Its county-based coordinators educate child-serving organizations about the importance of good oral health from a child’s earliest months. And it recruits dentists to serve more children who are eligible or enrolled in Apple Health for Kids, incentivizing their care by streamlining Medicaid reimbursements.[10]

“The goal is to work with all of the agencies that work with little children, going to them and explaining why it’s important to have early access to oral health care—instead of later, when issues can be more painful and traumatic. Talking about how in the future their overall health can be affected if those cavities continue.”

Anna Cruz, Access to Baby & Child Dentistry (ABCD) coordinator, Clark County

The need for community-based care

While parents and health professionals continue to look after the health of the kids in their lives, policymakers can also improve the oral health status of Washington’s children overall. There are several methods to strengthen the oral health network to provide access to the resources that shape oral health and well-being.

Dental therapists offer an evidence-based approach to providing community-based care. They are one of the most successful oral health interventions available to states looking to improve oral health outcomes.

A workforce enhancement similar to physician assistants or nurse practitioners, dental therapists join with hygienists and dental assistants under the supervision of a dentist. They’re already at work, or authorized to work, in 12 states.

The Swinomish Indian Tribal Community hired the first dental therapist to work in Washington state in January 2016. In 2017, the state Legislature formally recognized the sovereign right of Washington tribes to deliver community-based care with dental therapy, creating a broad path to better oral health on tribal lands throughout the state. Meanwhile, advocates have worked to authorize dental therapy on a statewide basis, and the Lower Elwha, Lummi, Colville, and Port Gamble S’Klallam tribes have added dental therapists to their health practices in four more locations, from the Inland Northwest to the Olympic Peninsula.

“There is sound evidence that dental therapists can improve access to care. In their first 10 years of work in Alaskan Native communities, dental therapists improved health outcomes. Individuals in these communities, who had little to no access to dental care locally prior to the introduction of dental therapists, were satisfied with the care they received—and no longer had to wait as long to receive it. Children and adults are getting more preventive care and keeping more of their natural teeth.”

Dr. Donald L. Chi, DDS, PhD, University of Washington School of Dentistry

Conclusion

Like a power grid, the health grid supplies kids and families with what every person needs to experience their optimal health, with the means of preventing adverse events, treating chronic conditions, and deploying the tools of the health profession to build a strong future for all of us.

The childhood experience of dental caries are too often understood as patient-level events that need attention by parents, providers and children themselves. Yet when the data shows consistent disparities dividing children by where they grew up, what they look like, or who their families are, then it’s clear that systematic inequalities in the health grid are creating these unequal outcomes.

In the face of these challenges, an array of tools is necessary. Community-level care by dental therapists can be a workforce enhancement that creates better care for all.

Thank you to the following individuals for informing the recommendations in this brief:

Donald L. Chi, associate professor, University of Washington School of Dentistry;

Anna Cruz, ABCD Clark County coordinator;

Gift-Noelle Wango, ABCD program supervisor, Snohomish Health District.

[1] , 2015-16.

[2] “Poor oral health can mean missed school, lower grades,” Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry, 3 University of Southern California, .

[3] The Journal of Human Resources, Feb. 2009.

[4] Washington Post, Feb. 28, 2007.

[5] Children’s Dental Health Project.

[6] Smile Survey, p. 4. The Smile Survey does not disaggregate Asian by ethnic groups. The Asian population is extremely diverse, and there is significant variation in outcomes and experiences for different Asian subgroups. The aggregate health data for this group often masks worse outcomes and barriers for Southeast Asian children and families, for example.

[7] Georgetown Center for Children and Families.

[8] Washington State Department of Health, May 29, 2019.

[9] University of Washington Center for Health Workforce Studies, November 2017.

[10] Pew Charitable Trusts.